Structuring Pages in HTML5

In addition to defining individual parts of your page (such as “a paragraph” or “an image”), HTML also includes a series of block-level elements used to define areas of a website (such as the header, navigation menu, main content column, and others). In this article, we examine how to plan a basic structure for a website to represent this layout.

A major benefit brought by HTML5 is that it allows us to structure documents in such a way that they have not only visual logic, but semantic clarity as well.

Basic Sections of a Document

Web pages can and will look quite different from one another, but they tend to share similar standard components—unless the page displays a video game or full-screen experience, is part of some kind of art project, or is simply poorly structured:

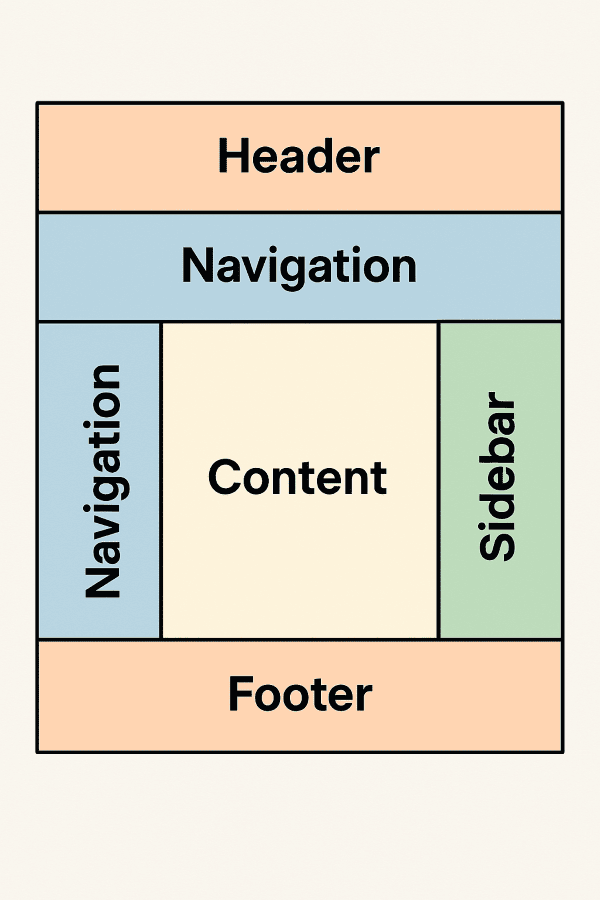

header – usually represented by a large band positioned at the top, with a big title and/or a logo. This is the place where key site-wide information is placed, and it typically repeats across all pages.

navigation bar – contains links to the main sections of the site, usually represented as button-style links. Like the header, this content generally remains unchanged from page to page. Many web designers consider the navigation bar part of the header, while others argue that separating the two improves accessibility, as screen readers can interpret them more effectively when distinct.

main content – a large central area that contains most of the page's content, such as a video, main article, map, or primary headings. This part of the site will definitely vary from page to page.

sidebar sections – consist of peripheral information, links, quotes, announcements, and other items related to the main page content or the overall site (such as a secondary navigation system).

footer – usually a band located at the bottom of the page, which may contain useful links, copyright notices, contact information, and more. The content of this element is typically identical across all pages of a site.

A typical website layout, commonly referred to as the "holy grail layout", looks like this:

Let's not forget that among Internet users, there are also people with disabilities for whom the visual design of a site may mean nothing.

For these categories of users, the way a site is structured matters greatly. If a page is not properly structured, there will be no content hierarchy and no clear logic.

When used correctly, these elements give the page a schematic structure that clearly and intelligently represents how the content is grouped. This makes the site more accessible and more engaging for both users and search engines. Additionally, a site with well-structured HTML code will be easier to style.

Therefore, in this article, we begin to study each structural element individually, starting with those that create sections in documents.

The Nav Element

The nav element represents a section of a page whose purpose is to establish links to other pages or to parts of the current page. Essentially, it is a section that contains navigation links.

Not all links on a page need to be contained within the nav element. This element is intended for sections that consist of large blocks of navigation.

This does not mean that the footer section, which usually contains several links, should group those links within a nav element. Using this tag in such a case is unnecessary.

The Article Element

The article and section elements sometimes create confusion for those who use them.

This element should be seen as a kind of autonomous container, which can have its own internal structure and content that can be distributed, copied (syndication), and reused. It could be a forum post, an article on a specific topic, a blog post, user-generated content, or any other form of independent content that, even if moved to another page, still makes sense. It is independent.

When multiple article elements are nested, the inner elements generally represent articles related to the main article.

When used for a main article on the page, it can be used together with the main tag, because this will not create a new section in the structure and will give the page more semantic meaning.

This element should be used with care, especially when it contains self-contained information.

The Section Element

Just like with the article element, there is some confusion about the appropriate time to use this element.

The section element represents a generic section of a document or application, a thematic grouping of content. Examples of sections include chapters of a book or a homepage divided into introductory sections of articles, news, and contact information.

When an element is needed only for styling purposes, authors are encouraged to use the div element. The section element is only necessary if its content should be explicitly listed in the document outline.

It is considered best practice to start each section with a heading.

The Aside Element

The aside element represents a section that should contain content tangentially related to the surrounding content and that can be presented separately from that content. Such sections are often represented as side elements in printed typography.

The element can be used for typographic effects, for quotes, for advertising, for a group of navigation elements (a sidebar menu), and for any other content that can be presented separately from the page content.

The positioning of this element on the page is very important, because semantically it represents much more than just a simple sidebar.

Non-semantic Elements

The block-level element <div> has no semantic meaning and is used as a container for other elements, in order to modify their presentation using CSS or to perform certain JavaScript tasks.

Authors are encouraged to see this element as a last resort when no other suitable element exists. What a good joke...

Using other elements instead of the old div leads to better accessibility for users and easier maintenance and updating of web pages.

The div tag should not be completely ignored. Many designers use the tag to apply CSS properties to a smaller or larger group of elements and sometimes even to the entire page.

The <span> element is non-semantic, inline, and should only be used if you can't think of a better semantic element to wrap your content or if you don't want to add any specific meaning.

The <hr> element creates a horizontal line in the document, which denotes a thematic shift in the text (such as a change of topic). Visually, it appears as a horizontal line, just like the one below.

What is "divitis" and how is it treated?

Incorrect example:

<div class="page">

<div class="header">

<div class="logo">Logo</div>

<div class="nav">

<div class="menu-item">Home</div>

<div class="menu-item">About</div>

<div class="menu-item">Contact</div>

</div>

</div>

<div class="content">

<div class="article">

<div class="title">What is divitis?</div>

<div class="text">Too many divs!</div>

</div>

</div>

<div class="footer">© 2025</div>

</div>

Correct example:

<main>

<header>

<h1>Logo</h1>

<nav>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

</header>

<section>

<article>

<h2>What is divitis?</h2>

<p>It is the excessive use of divs instead of semantic elements.</p>

</article>

</section>

<footer>

<p>© 2025</p>

</footer>

</main>

Divitis is a term used to describe a common mistake among less inspired or less trained authors—namely, the excessive use of div elements in web pages.

Divitis belongs to the same category as 'classitis' and 'span mania', both terms being suggestively used to describe the exaggerated and unnecessary use of certain tags or classes.

The Header Element

The header element has a semantic role; it does not alter the structure of the document in which it appears. It functions as an introduction (for the nearest sectioning element or root element), is located at the top of a page or section, and may contain a logo, navigation elements, an image, or the title of the respective section. It can also be used to wrap a search form or the introductory part of a sectioning element.

- Use of the element is not mandatory;

- It can be used multiple times on a page;

- Because it usually contains headings, it gives the false impression that it is a sectioning element.

The Main Element

This element wraps the dominant and unique content of the document and must be a primary hierarchical element, without accessible name or autonomous custom elements.

A primary hierarchical element has parents limited to the following elements: html, body, div, and form.

- Use of the element is not mandatory;

- It can be used only once on a page;

- It is highly semantic;

- It is not a sectioning element.

The Footer Element

The footer element has a semantic role and creates a footer for the page, for the nearest sectioning element or root element. It usually contains additional information about the element it belongs to (such as the article's author), links to related documents, copyright notices, etc. The author's contact information can be placed inside an address element within a footer element.

- Use of the element is not mandatory;

- It can be used multiple times on a page.

WAI-ARIA

Web Accessibility Initiative–Accessible Rich Internet Applications defines how to make web content and web applications more accessible to people with disabilities.

Web content accessibility is achieved through semantic information about widgets, structures, and behaviors, allowing assistive technologies to convey appropriate information to users with disabilities.

More information can be found here: